I started drafting this blog post in 2018, but didn’t have the heart to share it. I’ve revisited, revised, and updated it to tell my story a little more clearly for those of you who have been following my career.

A teacher is all I ever wanted to be. My childhood bedroom was decked out like a classroom, complete with a vintage desk, chalkboard, and carefully arranged grading area. I wrote tests for my family over concepts I learned in school and on PBS (what fun for them) and taught lessons to a very engaged audience of stuffed animals. As I grew older I considered other careers, but teaching seemed like the surest bet. I knew I would be good at it and that there was a need for passionate educators. I knew that I had the patience and creativity necessary to reach students. And perhaps most importantly, I didn’t care about being rich.

I did everything right. Well, I did everything I was told was right by my uneducated family. I went to college and studied what interested me most: English Literary Criticism with a minor in Women’s and Gender Studies. “Do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life!” my mother told me.*

I went to grad school in English Literature (slightly more practical than criticism or women’s studies, I thought). I considered a PhD, but heard horror stories of a market overrun with English doctoral candidates, fighting for positions in far-flung locales where they would then spend their days in a harried fever writing and researching during every moment not in the classroom. I didn’t want that. I’m not that competitive. I just wanted to teach. So I went to grad school again in an even more practical field: Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL). With a terminal M.A., I thought, I’ll definitely be able to continue doing what I love. And I did. My time at CMU was incredible. I taught and researched (as much or little as I wanted), presenting at conferences and learning more each day about my craft. I traveled to China and taught students in a university. I was happy.

Then I moved. I moved to California, throwing away my relatively steady lectureship in Michigan to follow my partner to Eureka. When I settled into this tiny corner of the coast, I found something I had heard endless rumors about before: the routine exploitation of adjunct labor. In Michigan I had been lucky. My office was full of full-timers with benefits. We had one-year or two-year contracts. We got yearly raises. Our conference travel was paid. My experience in California could not have been more different.

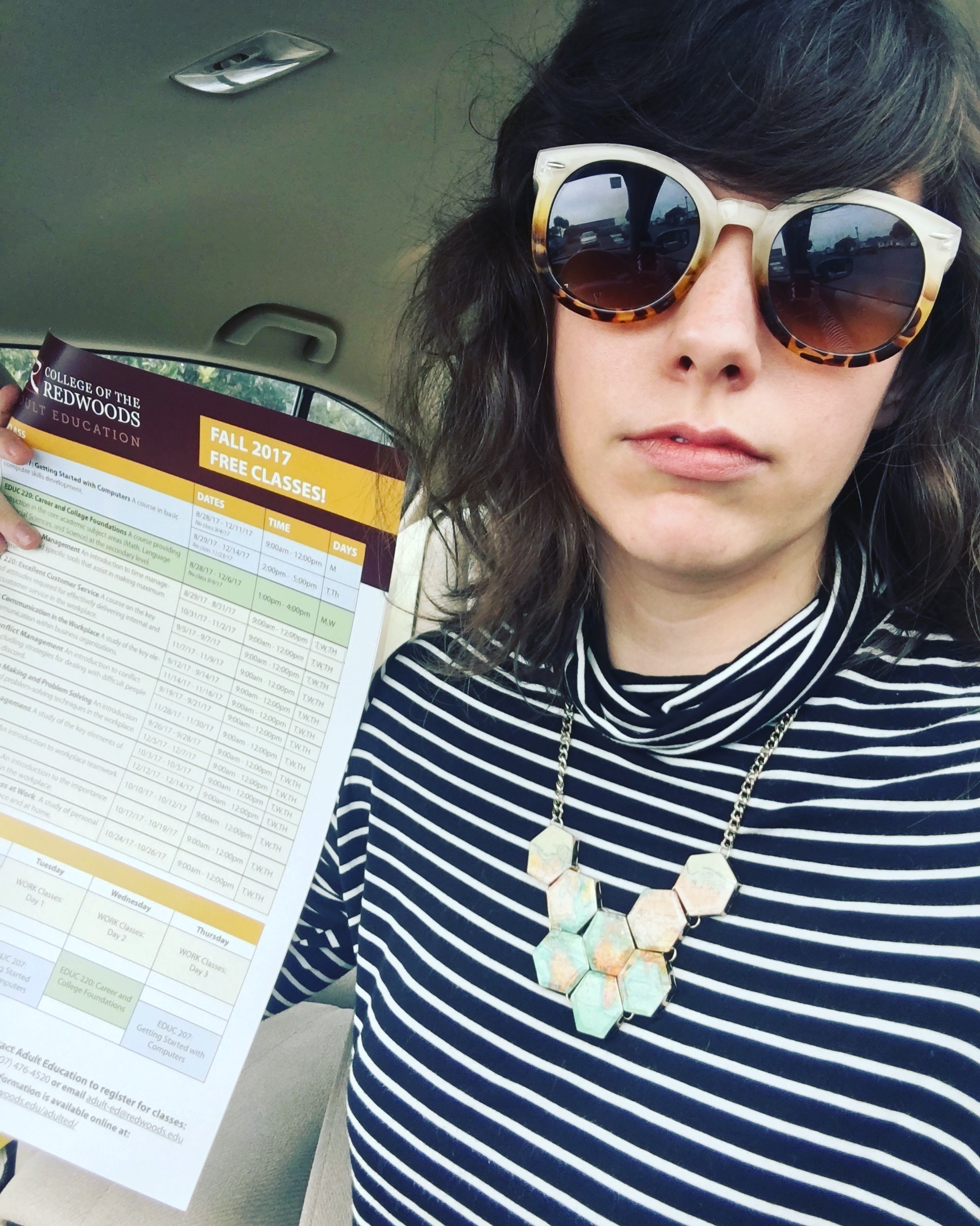

I began at a community college where adjuncts were given a cap on the number of hours they taught (to ensure that no benefits could ever be provided). Pay was based on literal hours in the classroom. If a class was cancelled for a holiday, that was a $0 day. Christmas break? Better save up! If students stopped showing up to your free classes (something common and completely outside the teacher’s control), the classes got cancelled — mid-semester with little to no notice. After a suite of my classes got cancelled all at once (the ones I marketed so cheerfully in the above photo), I started with the local CSU English Language Institute, which thankfully operated on a quarter system and could hire me on the following month. Somehow this unit functioned completely outside of union representation or requirements, and treated its teachers in a similar way. Pay was again hourly (and about half the rate of the community college, but with a few hours of prep paid each week). This was a great job, but the pay was worse than the community college and our enrollment dwindled, leaving the future of the unit up in the air.

Even after teaching multiple intensive English courses, tutoring at night, picking up a part-time job at the local yarn shop, and doing remote work for a number of companies (see my previous blog post), I was still far below the poverty level, making the equivalent of $12.50/hr (assuming I put in 40 hours/week of work, which is a low estimate). I did not have the support system to make this workable. I had to stop teaching for my survival.

Sidenote: These issues are systemic and not isolated to these institutions. I sincerely felt that both schools were doing the best they could with their resources, and I felt supported by my direct leadership. I didn’t take either job loss personally (but they did inspire me politically).

Next, I found a state job at the technician level that didn’t suit my skills or account for my education, but gave me pay, stability, and benefits that I had never had as an educator utilizing my three degrees. Shortly after I left the institute where I had been teaching, they lost their funding and closed down, leaving both teachers and students without a home. Although my new job was not a good fit, it was stable and I was grateful. My agency wanted to invest in my career development. They cared about what I wanted to do next. As a teacher, I would keep crossing my fingers for increased enrollment and in the case of my TESOL gigs, geopolitical favor. With state work, I could finally breathe easy. I knew I would have a paycheck next month. Despite all of my hard work and constant hustling, two master’s degrees, and aptitude in my field, this was a completely novel feeling.

When I first left the classroom, my friends and colleagues in academia asked in horror how I could possibly stop teaching. They were shocked that someone so driven and hardworking would quit something they were good at and had invested so much in. “Just try another semester,” they would say. “It’s all cyclical. Things will turn around,” they would reassure. But have things turned around? Across the country institutions are eagerly cutting humanities courses and English language institutes because they aren’t marketable or outwardly valuable. Of course, you could get lucky and work somewhere where you are valued. You could. Or you could lose it all, like I did, and start over. Either way, I’m here to say, you’ll be okay.

Ultimately, leaving the academy taught me that I’m worth more than a question mark at the end of each semester.

This isn’t the end of my story, and thankfully, I landed not only on my feet, but upright and upwardly mobile. I now have a career in California state government that I adore, where I use my skills, work with incredible people, and sleep easy knowing I’ll have a job tomorrow.

I will detail my transition out of academia and into civil service in my next blog post, where I will also discuss the endless transferrable skills current and former educators have that they may not realize they can unlock and apply outside the classroom. You’re worth money. You’re worth work-life balance. You deserve more, teacher friends.**

*K-12 education wasn’t immediately appealing to me, so I didn’t go the credential route as an undergraduate. This would haunt me for the rest of my career, as attaining a K-12 credential after finishing school requires that even an experienced teacher return to the classroom and do an entire unpaid year of student teaching, which I could never afford to do.

**If you’re in a wonderfully stable university teaching position with no fear of a budget cut or hateful dean, WONDERFUL! I am legitimately happy for you and wish you a joyful life. You deserve that in whatever form it takes. 😄

I am waiting with baited breath to read your next post. I’ve been teaching for almost 17 years and it is time to change careers.

LikeLike